On August 27, 2025, the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) dropped a major move: it sanctioned a Russian national, a North Korean operative, and two companies tied to a global network that stole over $2.1 billion in cryptocurrency in just the first half of the year. This wasn’t a one-off. It was the latest step in a relentless, year-long campaign targeting North Korea’s most dangerous and underreported revenue stream - crypto theft disguised as remote IT work.

Here’s the brutal truth: North Korea isn’t just hacking exchanges anymore. It’s embedding its agents inside U.S. tech companies - including crypto startups - using fake identities, stolen documents, and remote work platforms to steal data, demand ransom, and siphon off millions in stablecoins. And it’s working. The money doesn’t vanish into the blockchain. It gets converted to cash, shipped overseas, and funneled straight into weapons programs.

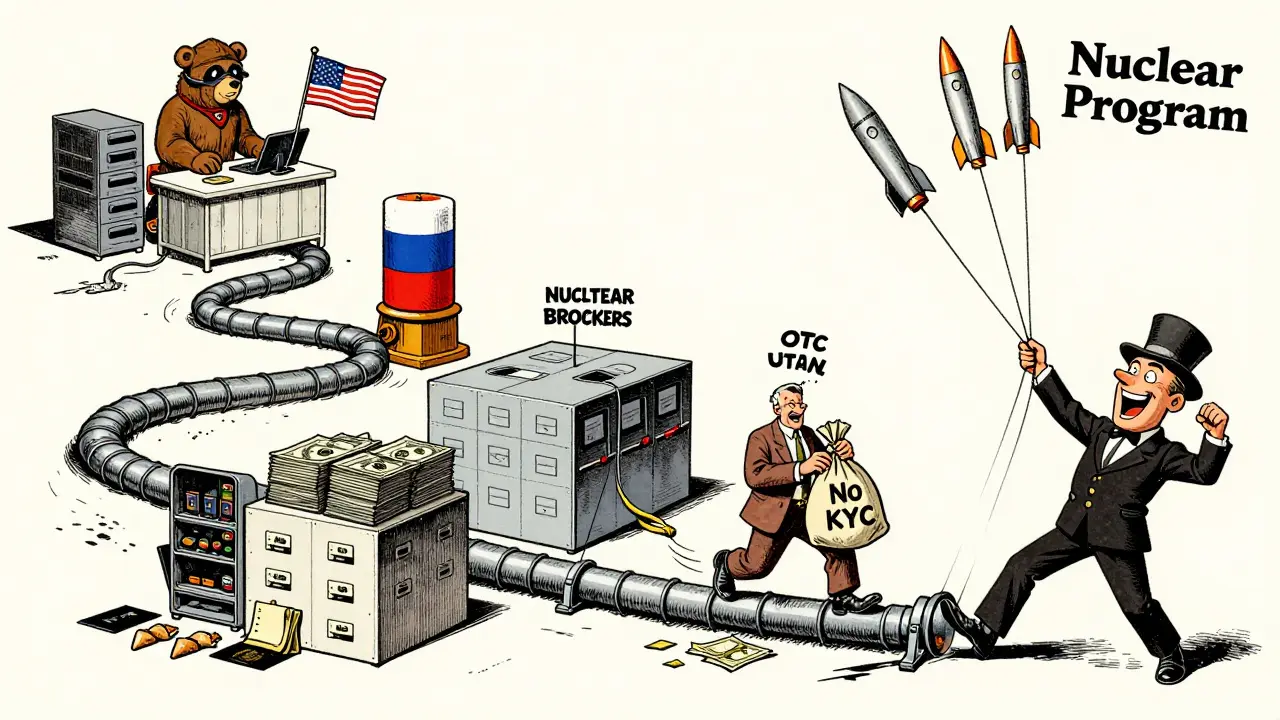

How North Korea’s IT Worker Scam Works

Imagine a freelance software developer on Freelancer.com, hired by a Silicon Valley startup to build a smart contract. They deliver on time. They’re responsive. They use GitHub with a clean history. They even have a Medium blog about Web3 architecture. Sounds legit, right? Except this person doesn’t exist.

They’re a North Korean operative. Their identity - ‘Joshua Palmer,’ ‘Alex Hong,’ or one of dozens of reused personas - was built from stolen personal data. Their resume? Fabricated. Their LinkedIn? Fake. Their work? Real enough to pass vetting. But while they’re coding, they’re also mapping the company’s security gaps, logging credentials, and installing backdoors.

These workers are placed in companies that rely heavily on remote teams - especially crypto firms where hiring is fast, background checks are light, and payroll is often done in USDC or ETH. Once they’re in, they start collecting payments. Not for work. For fraud. They invoice for services never rendered, or they’re paid for work that’s just a cover. The crypto hits their wallet. Then it moves - through dozens of intermediate addresses, mixing services, and self-hosted wallets - before landing in the hands of senior DPRK operatives like Kim Sang Man and Sim Hyon Sop, both already on OFAC’s sanctions list.

The Money Trail: From ETH to Cash

The stolen funds don’t stay digital. That’s the key. North Korea doesn’t need Bitcoin to buy missiles. It needs U.S. dollars. So the crypto gets converted.

Investigators found that Kim Ung Sun, one of the newly sanctioned individuals, personally handled over $600,000 in crypto-to-cash conversions. He used OTC brokers - some based in Russia, others in the UAE - who didn’t ask questions. These brokers, in turn, were linked to shell companies in China and Laos. The cash was then moved through third-country banks, often with forged invoices for ‘IT consulting’ or ‘software licensing.’

The Department of Justice filed a civil forfeiture case in June 2025, seizing $7.7 million in digital assets - including ETH, USDC, and even high-value NFTs - tied to this network. One wallet alone had over 120 incoming transactions from compromised U.S. companies. Each one was a small drip. Together, they made a flood.

Who Got Sanctioned? The Key Players

OFAC didn’t go after random addresses. They went after the people and companies making it possible:

- Vitaliy Sergeyevich Andreyev - A Russian national who helped move funds and provided infrastructure, including servers and IP addresses.

- Kim Ung Sun - The North Korean operative directly managing financial transfers from stolen crypto.

- Shenyang Geumpungri Network Technology Co., Ltd - A front company in China, posing as a legitimate IT outsourcing firm.

- Korea Sinjin Trading Corporation - A trading entity used to disguise crypto payments as legitimate business transactions.

These weren’t isolated actors. They were nodes in a network that also includes Korea Sobaeksu Trading Company, Chinyong Information Technology Cooperation Company, and at least seven other entities sanctioned since 2023. All of them operate under the same model: hire remote workers, collect crypto, launder it, send cash to Pyongyang.

Why This Is Different From Regular Hacking

Most cyberattacks are one-time hits: ransomware, phishing, data breaches. This is a system. It’s not just stealing money. It’s stealing trust.

North Korea’s IT workers aren’t breaking in. They’re being hired. They’re on Slack. They’re in Zoom meetings. They’re getting performance reviews. And while they’re doing real work - sometimes even good work - they’re gathering intel on internal systems, employee access levels, and wallet storage practices. One company lost $1.2 million not because their wallet was hacked, but because their ‘remote developer’ quietly copied the seed phrase during a system update.

It’s espionage disguised as outsourcing. And it’s working because no one expects a North Korean to be on their team.

The Global Web: Russia, China, UAE

This isn’t a North Korean problem. It’s a global blind spot.

The infrastructure supporting these operations spans continents. Russian servers host the fake GitHub profiles. Chinese firms supply the fake IDs and passports. UAE-based OTC brokers convert crypto to cash without KYC. And the money flows through shell companies in Laos and Vietnam.

OFAC’s August 2025 sanctions specifically named Russian and UAE-linked entities because they’re critical to the laundering chain. Without these third-country facilitators, the whole scheme collapses. That’s why the U.S. is now pressuring foreign governments - Japan, South Korea, and others - to shut down these cross-border pipelines.

Law enforcement agencies like the FBI and HSI have seized wallets, tracked transactions, and even worked with blockchain analytics firms like TRM Labs to build real-time dashboards of sanctioned addresses. The goal isn’t just to freeze funds - it’s to map the entire ecosystem so future sanctions can hit the next link before it even forms.

What This Means for Crypto Companies

If you run a crypto startup or hire remote developers, this isn’t a ‘foreign policy’ issue. It’s a security risk.

Here’s what you need to do:

- Verify identities beyond LinkedIn - Ask for government-issued ID, cross-check with phone records, and use third-party verification tools. Don’t rely on self-reported info.

- Monitor wallet activity - If a contractor’s payment address has ever been linked to a sanctioned entity (check OFAC’s list), cut ties immediately.

- Limit wallet access - Don’t give remote workers access to cold storage, admin keys, or multisig wallets. Use role-based access controls.

- Screen for red flags - Workers using only free email domains (Gmail, ProtonMail), no prior work history, or who refuse video interviews should raise alarms.

Companies that ignored these signs in 2024 are now facing lawsuits, regulatory fines, and reputational damage. One U.S.-based Web3 firm lost $3.4 million and had to shut down after their ‘lead blockchain engineer’ - later revealed to be a North Korean operative - drained their treasury wallet.

What’s Next?

OFAC isn’t done. In fact, they’re just getting started. The $2.1 billion stolen in 2025 is already being used to fund missile tests and nuclear development. The U.S. government has made it clear: if you’re helping North Korea launder crypto, you’re helping them build weapons.

More designations are coming. More arrests. More seizures. The blockchain is public. Every transaction leaves a trail. And with tools like TRM Labs and Chainalysis monitoring every movement, the days of hiding crypto theft behind fake identities are over.

The message is simple: If you’re working remotely for a company with ties to North Korea - even indirectly - you’re not just risking your job. You’re risking your freedom.

How did North Korea steal over $2.1 billion in crypto?

North Korea used remote IT worker schemes to infiltrate U.S. crypto and tech companies. Workers used fake identities to get hired, then stole data, copied wallet keys, and invoiced for non-existent services. Payments were made in USDC or ETH, then laundered through Russian, Chinese, and UAE intermediaries before being converted to cash and sent to North Korean military programs.

Who is Kim Ung Sun and why was he sanctioned?

Kim Ung Sun is a North Korean operative directly tied to converting stolen cryptocurrency into U.S. dollars. He facilitated at least $600,000 in transfers using front companies and OTC brokers. OFAC sanctioned him in August 2025 for his role in financing the DPRK’s weapons programs through crypto theft.

Can I get in trouble if I hire someone from North Korea unknowingly?

Yes. Even if you didn’t know, U.S. law requires companies to screen contractors against OFAC’s sanctions list. If you pay someone who’s later found to be linked to a sanctioned entity - even indirectly - you could face civil penalties, asset seizures, or criminal charges. Due diligence isn’t optional anymore.

What platforms are North Korean hackers using to find jobs?

They use global freelance platforms like Freelancer, Upwork, RemoteHub, CrowdWorks, and WorkSpace.ru. They also create fake GitHub profiles and Medium blogs to build credibility. Many use stolen identities from Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia to appear as local workers.

How can I check if a contractor is linked to North Korea?

Use OFAC’s sanctions list and blockchain analytics tools like TRM Labs or Chainalysis. Check the crypto addresses they use for payments. If any address has ever interacted with a sanctioned wallet (like those linked to Kim Sang Man or Andreyev), avoid them. Also, verify identity with multiple documents and video calls - never rely on documents alone.